Scientists witness surprising behavior from Dalquest Desert Research Station spider

Almost three years ago, the taxonomy world celebrated the recognition of a new family of spiders which had been discovered on Midwestern State University’s Dalquest Desert Research Station near the Big Bend area of Texas and in the Chihuahuan Desert of Mexico.

Top araneologists from around the world studied the newcomer that was found cohabitating with three species of harvester ants. They named the spider Myrmecicultor chihuahuensis – “myrmex” being the ancient Greek word for ant, and “cultor,” Latin for worshiper or follower – because of the unusual living arrangement with the ants.

Now the ugly truth has come out. The spiders don’t worship the ants. They eat them.

This surprising discovery was made as Midwestern State’s Norman Horner, professor emeritus of biology, and former president and chemistry professor Jesse Rogers, with Paula Cushing of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science and Adrian Brückner of the California Institute of Technology, were determining if the chemical nature of the two was what allowed them to live together. They suspected the ants did not bother the spiders because they had similar odor compounds. They also hypothesized that because of the spiders’ small size, less than three millimeters, they preyed on other insects living with the ants.

Imagine their surprise when they saw who was preying on whom.

“We were totally shocked that the spiders were actually feeding on the ants,” Horner said. “The ants are more than twice the size of the spiders, but the spider has developed a method of coming up behind the ant and biting it on the hind leg.”

The aggressive behavior was witnessed in October of 2020 at the Dalquest Desert Research Station when two spiders were placed in a Pyrex dish with a thin layer of soil at the bottom.

MSU Texas Professor Emeritus of Biology Norman Horner (left) and Paula Cushing of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

Ants were then introduced into the dish with the resulting behavior observed and filmed using red light. The spiders did not approach an ant frontally. They would follow the ant, rush forward and bite the ant between leg segments, then back off waiting for the venom to act, usually taking a minute to paralyze the ant. The spider would re-approach the ant and insert its fangs behind the head of the ant, lift it, and carry it to a safe place to feed, then begin its feast between the ant’s head and thorax.

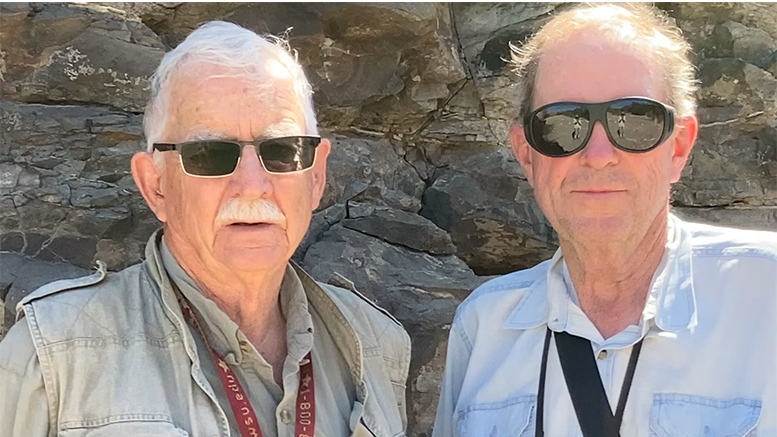

MSU Texas Professor Emeritus of Biology Norman Horner (left) and Jesse Rogers, former MSU Texas president and chemistry professor, at the Dalquest Desert Research Station.

The scientists also witnessed what happened when an unbitten ant approached a spider carrying a paralyzed ant. The spider immediately repositioned, turned, or flipped itself so the active ant would encounter the paralyzed nest mate, rather than the spider. “The spider easily manipulated the paralyzed ant even though it was larger than the spider itself and used it as a shield,” Horner said.

The new findings were published in an article titled “Trophic specialization of a newly described spider ant symbiont, Myrmecicultor chihuahuensis (Araneae, Myrmecicultoridae),” in the August 2022 issue of The Journal of Arachnology. Cushing, Brückner, Rogers, and Horner are credited as authors.

Over the course of two nights, two female spiders killed nine ants. The article states that this level of “carnage, or ‘over-kill’” has been documented before in other species and may be a strategy related to the specialized hunting of dangerous prey, or it may be due to the “small size of the enclosure and the inability of the spiders or ants to escape one another.”

The spider was initially found in 1999 by Horner’s student Greg Broussard, who now teaches biology at Central New Mexico Community College in Albuquerque. The process to identify the spider and formally recognize the new family took almost 20 years.